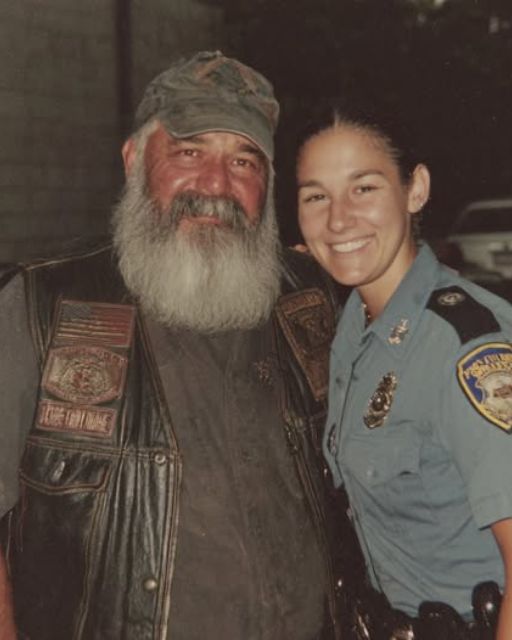

The biker stared at the cop’s nameplate while she cuffed him—it was his daughter’s name.

Officer Sarah Chen had pulled me over for a broken taillight on Highway 49, but when she walked up and I saw her face, I couldn’t breathe.

She had my mother’s eyes, my nose, and the same birthmark below her left ear shaped like a crescent moon.

The birthmark I used to kiss goodnight when she was two years old, before her mother took her and vanished.

“License and registration,” she said, professional and cold.

My hands shook as I handed them over. Robert “Ghost” McAllister.

She didn’t recognize the name—Amy had probably changed it. But I recognized everything about her.

The way she stood with her weight on her left leg.

The small scar above her eyebrow from when she fell off her tricycle.

The way she tucked her hair behind her ear when concentrating.

“Mr. McAllister, I’m going to need you to step off the bike.”

She didn’t know she was arresting her father. The father who’d searched for thirty-one years.

Let me back up, because you need to understand what this moment meant.

Sarah—her name was Sarah Elizabeth McAllister when she was born—disappeared on March 15th, 1993.

Her mother Amy and I had been divorced for six months. I had visitation every weekend, and we were making it work.

Then Amy met someone new. Richard Chen, a banker who promised her the stability she said I never could.

One day I went to pick up Sarah for our weekend, and they were gone. The apartment was empty. No forwarding address. Nothing.

I did everything right.

Filed police reports. Hired private investigators with money I didn’t have.

The courts said Amy had violated custody, but they couldn’t find her.

She’d planned it perfectly—new identities, cash transactions, no digital trail.

This was before the internet made hiding harder.

For thirty-one years, I looked for my daughter.

Every face in every crowd.

Every little girl with dark hair.

Every teenager who might be her.

Every young woman who had my mother’s eyes.

I never remarried. Never had other kids.

How could I? My daughter was out there somewhere—maybe thinking I’d abandoned her.

Maybe not thinking of me at all.

“Mr. McAllister?” Officer Chen’s voice brought me back. “I asked you to step off the bike.”

“I’m sorry,” I managed. “I just—you remind me of someone.”

She tensed, hand moving to her weapon. “Sir, off the bike. Now.”

I climbed off, my sixty-eight-year-old knees protesting.

She was thirty-three now. A cop.

Amy had always hated that I rode with a club, said it was dangerous.

The irony that our daughter became law enforcement wasn’t lost on me.

“I smell alcohol,” she said.

“I haven’t been drinking.”

“I’m going to need you to perform a field sobriety test.”

I knew she didn’t really smell alcohol. I’d been sober for fifteen years.

But something in my reaction had spooked her, made her suspicious. I didn’t blame her.

I probably looked like every unstable old biker she’d ever dealt with—staring too hard, hands shaking, acting strange.

As she ran me through the tests, I studied her hands.

She had my mother’s long fingers. Piano player fingers, Mom used to call them, though none of us ever learned.

On her right hand, a small tattoo peeked out from under her sleeve.

Chinese characters. Her adoptive father’s influence, probably.

“Mr. McAllister, I’m placing you under arrest for suspected DUI.”

“I haven’t been drinking,” I repeated. “Test me. Breathalyzer, blood, whatever you want.”

“You’ll get all that at the station.”

As she cuffed me, I caught her scent—vanilla perfume and something else, something familiar that made my chest ache.

Johnson’s baby shampoo.

She still used the same shampoo.

Amy had insisted on it when Sarah was a baby, said it was the only one that didn’t make her cry.

“My daughter used that shampoo,” I said quietly.

She paused. “Excuse me?”

“Johnson’s. The yellow bottle. My daughter loved it.”

She said: “Don’t fool me.”

“I’m not. I swear I’m not. You were born March 12, 1990. You had a stuffed bunny named Bramble you took everywhere. You used to say ‘tick-tock’ instead of ‘goodnight’ for some reason. And you fell off your trike trying to race the neighbor boy, remember? That scar on your eyebrow came from that.”

She blinked hard. Her grip on my elbow loosened.

“I think you have the wrong person,” she said, but her voice wasn’t as certain now.

“My name is Sarah Chen. My dad is Richard Chen.”

“And your mom?” I asked.

“Amy Chen. She passed two years ago. Cancer.”

That hit like a sledgehammer. Amy was gone. No chance to confront her, to ask why. To yell. Or forgive.

“Did she ever mention a man named Robert McAllister?” I asked.

She looked at me like I’d just torn the ground out from beneath her.

“I found a box in her closet after she died,” she said slowly. “Letters. Old photos. One of them was of a man on a motorcycle, holding a baby. The baby looked like me.”

I swallowed the lump in my throat. “That was me. That was you.”

She stood there frozen. The cruiser’s lights still flashing. Cars passing us on the highway, oblivious.

“I’m not drunk,” I said again. “Just shaken.”

She looked down at her clipboard, then back at me. “We’ll do the test at the station. But…I want to hear more.”

They booked me, of course. Standard protocol. I didn’t argue.

I blew a perfect 0.00 into the Breathalyzer. Blood test came back clean, too.

An hour later, she came into the holding room with a paper cup of coffee and sat across from me.

“You called me Sarah McAllister.”

“That’s your birth name.”

“And you’re telling me I’m your daughter.”

“I’m not telling. I’m remembering. Reaching.”

She pulled out her phone and showed me a grainy old photo.

“Is this you?”

It was. Me and her in front of a Christmas tree. She was three, wearing a reindeer sweater. I looked thirty years younger, hair dark and wild.

“My mom said he was dangerous. That he abandoned us.”

I closed my eyes. “I’d never abandon you. She took you and ran. I tried everything. I never stopped looking.”

She stared at me for a long time.

Then, quietly: “My middle name is Elizabeth. My mom said I was named after her favorite book character. But… she used to call me ‘tick-tock’ sometimes, and I never knew why.”

I laughed softly. “You couldn’t pronounce ‘night-night.’”

She didn’t smile, but her eyes glistened.

The next week, I got a letter in the mail from her.

It wasn’t long. Just a page. But she said she’d looked up court records. She’d contacted one of my old friends, who confirmed my story. She was angry, confused, but wanted to meet again—off duty.

We started with coffee. Then lunch.

She told me about her life. Her career. How strict Richard had been. How Amy had always seemed nervous when her past came up.

I told her about the bar I ran now, the sober biker club I mentored, how I’d tried to stay clean and useful.

One day she brought a photo of her mom in her final days. I cried. Not out of hate. Just the weight of it all.

Another week, she brought a DNA kit.

When the results came back, she called me. Voice shaking.

“It says we’re a 99.99% match.”

“I know.”

Silence.

Then she whispered, “Hi… Dad.”

That moment healed thirty-one years of silence.

Not overnight. But it cracked something open.

She started visiting more. Brought her fiancé one evening—a quiet nurse named Rebecca who seemed to understand the whole mess without needing details.

I was invited to their wedding. Sat in the second row.

When they had their daughter—my granddaughter—they named her Elise, after my mother.

Now, on Sundays, they come by the bar. I grill burgers out back. Sarah sometimes brings old photos she found. I bring out the baby pictures she never got to see.

The birthmark is still there, under her ear.

But now she wears her hair up.

Wants the world to see it.

Wants the world to know where she came from.

If you take anything from this story, let it be this—sometimes the truth takes the long road home.

But when it arrives, even in cuffs, it can still set you free.

Please share this if it moved you. You never know who’s still searching.