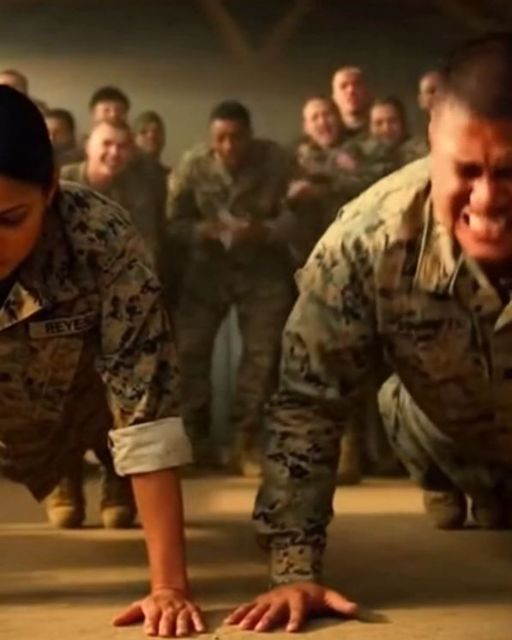

The whole platoon was watching. It was hot, the air thick with dust and boredom. Mark, who could bench press a truck, got in my face and said no woman could hang with him. Twenty bucks said I couldn’t beat his push-up record. I said make it fifty.

We started. The guys were hooting, all of them betting on him. For the first fifty, we were neck and neck. At sixty, I could hear him start to grunt. I was still smooth. At seventy, his arms were shaking hard. I was in the zone.

He collapsed at seventy-four. Just dropped flat on the dirt floor of the barracks. The whole room erupted, guys slapping my back, passing me money. I stood up, grinning, ready to gloat. But Mark didn’t get up. He just lay there, face down. I saw the platoon sergeant walk over to kick his boot, to tell him to get up.

But I got a look at the back of his neck as he lay there. Under his hairline, almost hidden, was a tiny, dark purple mark. It looked like a spiderweb. We saw a training film about this. That mark doesn’t come from getting hit. It’s a sign of a slow bleed, the kind you get from a shockwave, when your brain slams against your skull.

My grin vanished. The fifty-dollar bill in my hand felt like it was on fire.

“Sarge, wait,” I said, my voice barely a whisper.

Sergeant Reyes stopped, his boot hovering over Mark’s. He gave me an annoyed look.

“What is it, Corporal?”

I pointed, my own hand trembling slightly. “The back of his head. The mark.”

He crouched down, squinting. The other guys in the platoon went quiet, the celebratory mood evaporating like a puddle in the desert sun.

They saw it too. A collective, quiet gasp went through the room.

That mark had a name. They called it Battle’s Sign. It meant a basilar skull fracture. It meant TBI. Traumatic Brain Injury.

Sergeant Reyes didn’t hesitate for another second. He was on his radio, his voice calm and urgent, calling for a medic.

“Don’t move him,” he ordered the room. “Nobody touches him.”

The guys who were just laughing at Mark’s failure now stood in a silent, horrified circle. The bravado, the competition, all of it felt so stupid. So incredibly, horribly small. I knelt down a few feet away, my heart pounding in my ears. The push-up contest didn’t cause this. It was a symptom of something that had already happened.

The strain of the contest was just the final straw that broke something already fractured.

The medics arrived in what felt like seconds. They were professional, quiet, moving with a purpose that made our barracks bravado feel like a child’s game. They carefully fitted a neck brace on Mark and lifted him onto a stretcher. As they carried him out, his eyes were closed, his face pale under his tan.

I was the last one to see him go. I felt a profound, sinking guilt.

The fifty dollars was still clutched in my fist. I looked at the crumpled bill, the face of Ulysses S. Grant staring up at me, and I felt sick.

The next day, a heavy quiet hung over the platoon. No one talked about the contest. No one joked. Mark’s empty bunk was a constant, silent accusation. I tried to find out how he was doing, but all I got was the standard military line: “He’s being evaluated.”

I couldn’t let it go. I took the fifty-dollar bill and went to the on-base medical center. A stern-faced nurse at the front desk looked at me over her glasses.

“I can’t give you any information on another soldier’s condition,” she said flatly.

“I’m not asking for details,” I pleaded. “I just… I need to know if he’s okay. I was there.”

She saw something in my eyes, maybe desperation, maybe the guilt I was trying so hard to hide. Her expression softened just a little.

“He’s stable,” she said, her voice low. “But he’s been moved to the TBI clinic for further observation.”

TBI clinic. The words hit me like a physical blow. It was real.

I walked out into the harsh sunlight, feeling lost. I found myself at the small chapel on base, a place I hadn’t been to since basic training. I sat in an empty pew, the cool air a relief from the heat. I unfolded the fifty-dollar bill and laid it on the bench beside me.

What was I supposed to do with this? It wasn’t a prize. It felt like blood money.

“That’s a heavy-looking fifty dollars.”

The voice made me jump. It was Sergeant Reyes, standing in the aisle. He wasn’t in uniform, just a plain t-shirt and jeans. He looked older, more tired than I’d ever seen him.

He sat down in the pew across from me.

“It wasn’t your fault, Corporal,” he said quietly.

“But I pushed him,” I said, my voice cracking. “I saw him struggling, and I kept going. I wanted to win.”

“We all did,” he admitted. “We all saw it. None of us knew.”

He told me he had pulled Mark’s file. About a year ago, during his last tour, Mark’s vehicle had been hit by an IED. It was a close call, but everyone walked away. The official report said “no significant injuries.” Mark had been cleared for duty after a 24-hour observation.

No significant injuries. Except for a brain that got violently shaken inside his skull.

“He never said a word,” Sergeant Reyes said, shaking his head. “He just got more obsessed with being the strongest, the toughest. Like he had something to prove.”

He was trying to prove he wasn’t broken. He was trying to convince himself.

And we had all bought into it. We celebrated his strength, never once thinking it was a desperate mask for a hidden wound.

“What happens to him now?” I asked.

“They’ll run tests,” he said. “Best case, he gets treatment, maybe gets reassigned to a desk job. Worst case… a medical discharge.”

A medical discharge. For a guy like Mark, whose entire identity was wrapped up in being a soldier, that was a death sentence.

I left the chapel with a new resolve. The guilt was still there, but now it was mixed with a sense of responsibility. I had to do something.

My first step was trying to contact his family. It took some doing, bending a few rules and calling in a favor with a clerk in the administrative office, but I finally got a number for his sister. Her name was Clara.

I called her that night from a payphone, my hands sweating. I explained who I was, my voice faltering as I described the push-up contest.

I expected her to be angry, to yell at me. But she just sighed, a long, weary sound that spoke of months, maybe years, of worry.

“I knew something was wrong,” she said, her voice soft and sad. “He hasn’t been the same since he got back. He gets these terrible headaches. He forgets things. And the temper… he was never an angry person before.”

She told me about their life back home. Their parents had passed away years ago. It was just the two of them. She was a single mom, working two jobs to make ends meet, and Mark sent most of his paycheck home to help her with her son.

His pride, his refusal to admit he needed help, wasn’t just about his career. It was about taking care of his family.

“He was so afraid,” Clara said, her voice breaking. “Afraid they’d find out something was wrong and kick him out. He said he couldn’t let us down.”

After I hung up, I sat in the dark for a long time. I looked at the fifty-dollar bill in my hand. It was such a pathetic amount of money in the face of their struggle. But it was a start.

The next day, I took the fifty dollars to the base post office and bought a money order. I put it in an envelope with a short, simple note. “For your son. From a friend of Mark’s.” I sent it to Clara’s address.

It wasn’t enough, but it was something I could do. It was a way of turning that tainted prize into something better.

A week later, they let me see Mark. He was in a quiet room in the TBI clinic. The place was calm, a stark contrast to the noisy barracks. He was sitting up in bed, staring out the window. He looked smaller, less intimidating without his uniform.

“Hey,” I said from the doorway.

He turned, and I saw a flicker of shame in his eyes.

“Heard you set a new platoon record,” he said, trying for a joke. It fell flat.

“Doesn’t count,” I said, walking in and pulling up a chair. “The competition was compromised.”

He managed a weak smile. We sat in silence for a minute.

“I’m sorry, Mark,” I said finally. “For pushing you. For not seeing…”

“It’s not your fault,” he cut me off, his voice rough. “It’s mine. I knew something was wrong. I just… I was too stupid and proud to say anything.”

He told me about the headaches, the dizziness, the moments when words would just disappear from his mind. He told me about the constant fear that someone would find out he wasn’t the man he used to be.

“That day,” he said, looking at his hands, “I just wanted to prove I could still hang. That I was still the strongest.”

“You are strong, Mark,” I told him, and I meant it. “Admitting you need help? That’s the hardest thing in the world. That takes a different kind of strength.”

I started visiting him every day after my duties. We talked. Not about the army, but about regular stuff. His nephew’s Little League games, the clunker car I was trying to keep running, our favorite bad movies. I brought him magazines and contraband snacks from off-base.

Slowly, I saw the old Mark, the one from before the IED, start to peek through the cracks in his tough-guy armor. He had a dry sense of humor and a surprising love for old black-and-white films. He was a good person who had been trying to carry an impossible weight alone.

One afternoon, I arrived to find Sergeant Reyes in the room. They were talking quietly. Mark was going before a medical review board the following week. They were going to decide his future.

“They’re going to kick me out,” Mark said after the sergeant left. His voice was flat, defeated. “And that’ll be it. No more paycheck. No more insurance. What is Clara going to do?”

That’s when I saw the twist, the one that wasn’t about some dramatic plot point, but about a simple, karmic truth. The system was about to fail him because he had tried too hard to uphold its ideals of strength and silence.

“No,” I said, a sudden fire in my belly. “They’re not.”

I spent the next few days on a mission. I talked to Sergeant Reyes. I talked to the platoon. I even tracked down a couple of guys from Mark’s old unit who had been in the vehicle with him during the IED blast. I collected statements. I wrote down everything Mark had told me, everything his sister had told me.

On the day of the review board, I put on my dress uniform and stood outside the hearing room. When Mark came out, he looked pale.

“They want to talk to you,” he said, surprised. “And Sergeant Reyes.”

I walked in and stood before three stern-faced officers. I told them everything. I told them about the push-up contest, not as an excuse, but as evidence of a soldier desperately trying to measure up to a standard he thought was expected of him. I told them about his pride, about his family, about his fear.

“Specialist Mark isn’t a broken soldier, sirs,” I said, my voice steady. “He’s a wounded one. And he was wounded in the line of duty. His only failure was in thinking he had to hide that wound from us, his family.”

Sergeant Reyes spoke after me, confirming the details of the IED incident and Mark’s exemplary record before it. He talked about how the culture of “sucking it up” can sometimes cause more damage than any bomb.

Two weeks later, the decision came down. Mark was not going to be unceremoniously discharged. He was granted an honorable medical retirement with full benefits and access to the best TBI treatment programs the military had to offer. They also retroactively awarded him a Purple Heart, acknowledging the injury he sustained in that blast a year ago.

The day he was leaving the base, the whole platoon was there to see him off. There were no jokes, no bravado. Just handshakes, back slaps, and genuine words of respect. He was no longer the strongest man on base because he could lift the most weight. He was the strongest because he had faced his own vulnerability and survived.

He pulled me aside before he got into the car with his sister, who had flown in to drive him home.

“Clara told me about the money order,” he said, his eyes shining with unshed tears. “Fifty bucks.”

He reached into his pocket and pulled out a worn, creased fifty-dollar bill. It was the one I’d won from him. He must have gotten it back from the pot.

“I think this belongs to you,” he said, trying to hand it to me.

I pushed his hand back gently.

“No,” I said. “It belongs to us. Use it to take your nephew out for ice cream.”

He smiled, a real, genuine smile. “Thank you, Anna.”

“Thank you, Mark,” I replied.

We learn in the military that strength is about pushing forward, about never showing weakness, about being harder than the world around you. But that day, watching Mark drive away toward a new beginning, I understood the truth.

True strength isn’t about how much you can lift or how many push-ups you can do. It’s not about hiding your scars so no one can see them. Real strength is about having the courage to let someone see your wounds, and the compassion to help heal the wounds of others. It’s about realizing that the heaviest things we carry are the ones no one can see, and the strongest people are the ones who help each other carry the load.