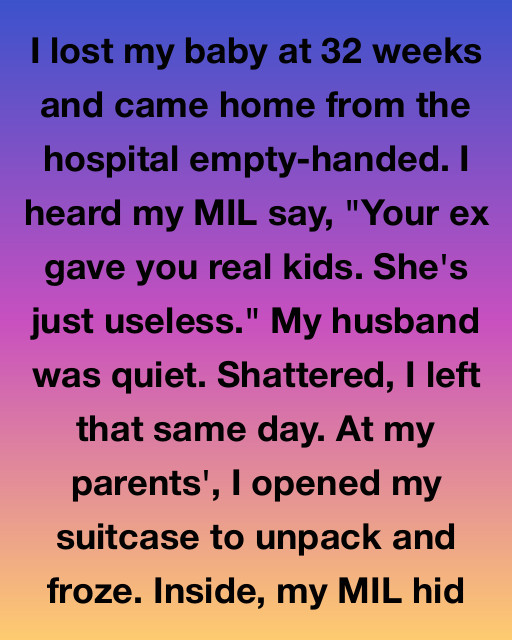

I lost my baby at 32 weeks and came home from the hospital empty-handed. The house, which was supposed to be filled with the soft sounds of a nursery, felt like a hollow tomb. I was moving through a fog of grief, my body still aching and my mind refusing to accept that my daughter, Willow, was gone. My husband, Callum, was like a ghost himself, wandering from room to room with a thousand-yard stare.

His mother, Margaret, had moved in “to help,” but her presence felt more like a heavy shroud. She had never liked me, mostly because she remained obsessed with Callum’s ex-wife, Sarah, who had given her two grandsons. To Margaret, I was just the second wife who worked too much and, now, the woman who couldn’t bring a child home. I was sitting in the darkened hallway, leaning against the wall for support, when I heard her voice drifting from the kitchen.

“You have to be practical, Callum,” she whispered, though her voice carried sharply. “Your ex gave you real kids, healthy boys who are actually here. She’s just useless; she can’t even do the one thing a woman is meant to do.” I waited for the explosion, for Callum to defend me, or for him to tell her to leave. But the silence that followed was deafening.

Callum didn’t say a word. He didn’t even sigh. That silence was the sharpest blade I had ever felt, cutting through the last bit of strength I had left. I didn’t scream, and I didn’t confront them. I simply walked back to our bedroom, pulled a suitcase from under the bed, and packed whatever my hands touched first.

I left that same day while they were out picking up the boys from school. I couldn’t breathe in a house where my worth was measured by my trauma. The drive to my parents’ house was a blur of rain and tears, my hands gripping the steering wheel until they turned white. My mom met me at the door, her eyes filling with tears the moment she saw my face, and she didn’t ask a single question.

She led me to my old childhood bedroom, a place that felt like a sanctuary after the war zone I had just fled. I sat on the edge of the twin bed, staring at the worn suitcase I had thrown onto the rug. My heart was a lead weight in my chest. I eventually reached for the zipper, needing to find a change of clothes so I could wash the scent of the hospital off my skin.

At my parents’, I opened my suitcase to unpack and froze. Nestled right on top of my folded sweaters, my MIL had hidden a thick, cream-colored envelope and a small, hand-knitted baby blanket I had never seen before. My first instinct was to throw it across the room, thinking it was some cruel parting gift or a list of reasons why I failed. But as I picked up the envelope, I noticed it was addressed to me in a shaky, elegant handwriting that didn’t look like Margaret’s usual aggressive scrawl.

Inside the envelope was a collection of medical records from thirty-five years ago and a long, handwritten letter. I began to read, and the world around me seemed to tilt. The letter wasn’t from Margaret to me; it was a copy of a letter Margaret had written to her own mother decades ago. It detailed the three babies she had lost before she finally had Callum.

She described the exact same hollow feeling I was experiencing—the feeling of being “useless” and the crushing silence of a home without a heartbeat. The records showed that Margaret hadn’t been the “perfect mother” she pretended to be; she had struggled with the same heartbreak I was facing. But then I saw a second note, written on a fresh piece of stationery, dated the day I came home from the hospital.

“I said those things to Callum because I wanted him to break,” the note read. “I wanted him to stand up and be the man I wish his father had been for me. I was cruel to you because seeing your pain reminded me of the years I spent pretending I was fine when I was dying inside.” It was a confession wrapped in a tragedy. She had been projecting her own unresolved grief onto me for years, using me as a punching bag for the anger she still felt toward her own past.

When I reached the bottom of the suitcase, tucked into the side pocket was a small digital recorder. I pressed play, expecting more vitriol. Instead, I heard Callum’s voice, recorded only an hour after I had left. He wasn’t talking to his mother; he was talking to the empty nursery.

“I couldn’t say anything, Willow,” he sobbed into the recorder. “If I opened my mouth, I would have fallen apart, and I had to be strong for your mom. But I failed her. I let my mother say those things because I was too weak to even stand up.” He went on for ten minutes, pouring out the grief he had been hiding behind his silence, explaining how he felt like he had lost two people—his daughter and the wife he didn’t know how to comfort.

I sat on the floor of my bedroom, the letter in one hand and the recorder in the other. I realized that grief is a labyrinth, and we all get lost in different corners of it. Margaret had become a villain because she never allowed herself to be a victim. Callum had become a ghost because he thought he had to be a pillar of stone. And I had become a fugitive because I thought I was the only one mourning.

I called Callum that night. We didn’t talk about his mother at first. We talked about Willow. We talked about the color of her hair and the way the room felt when she was still kicking. For the first time, the silence between us wasn’t a wall; it was a bridge. He told me that after I left, he finally told his mother to move out, and she hadn’t fought him on it.

She had handed him the suitcase she had “packed” for me, knowing I would leave. She knew that her presence was the poison, and in her own twisted, broken way, she had provided the antidote in that letter. She had given me the one thing I needed: the knowledge that I wasn’t “useless,” and that even the strongest-seeming women were built on a foundation of hidden cracks.

A week later, I went back home. The nursery door was closed, but the house felt warmer. Margaret didn’t come by, but she sent a small bouquet of willow branches for our garden. We planted them in the backyard, a living memorial for the daughter we wouldn’t get to raise. We were still broken, but we were broken together, which made the pieces much easier to carry.

I learned that day that people often speak from their own wounds, not from your reality. When someone is cruel to you in your darkest moment, it’’s usually because they are terrified of the darkness they see reflected in your eyes. My mother-in-law wasn’t a monster; she was a woman who had been taught that vulnerability was a weakness, and she had spent a lifetime paying the price for that lie.

Life doesn’t always give us a happy ending where everything is fixed, but it does give us moments of clarity. Strength isn’t about how much you can endure in silence; it’s about having the courage to speak your pain out loud. I wasn’t useless because I lost a child. I was a mother who had loved someone she never got to meet, and that love was the most useful thing I had ever created.

We still have the knitted blanket. It sits on a chair in the room that would have been hers. Sometimes I look at it and think about the woman who made it, and the three babies she lost before she had the son who eventually became my husband. It reminds me that we are all survivors of things people never see, and that the best way to honor our losses is to be kinder to the people who are still here.

If this story reminded you that you aren’t alone in your struggles, please share and like this post. We never know what kind of suitcases people are carrying or what’s hidden inside them. Would you like me to help you find the words to reach out to someone you’ve been struggling to understand?