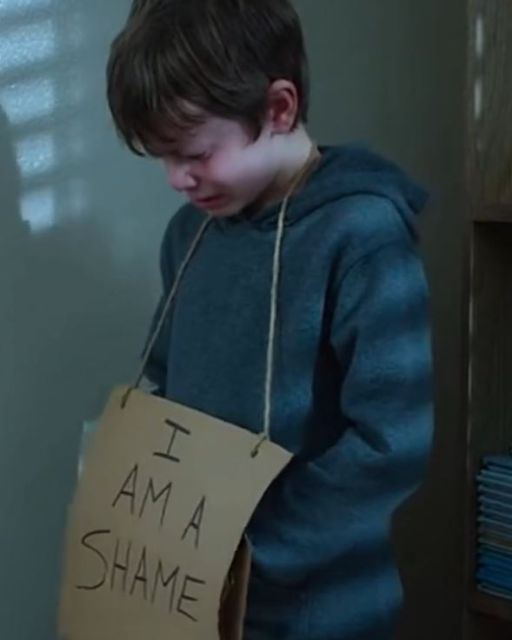

My son, Toby, was shaking in the corner. He’s eight. The piece of cardboard around his neck was bigger than his chest. Mrs. Halloway had written the words herself in thick black marker. He’d spilled some paint. He has dyslexia and gets his hands mixed up when he’s nervous. We’d told her that. She didn’t care. She called him a “disruption.”

I got a text from the school janitor. I was at the shop, rebuilding a clutch. I was there in five minutes.

I walked down the hall. My boots were heavy on the floor. The receptionist yelled something about a visitor’s pass. I didn’t stop. I pushed the door to Room 402 open so hard it hit the wall. The kids all gasped. Halloway stood up, her face tight with anger. “You can’t just barge in here!”

I didn’t look at her. I looked at my boy. I walked over, knelt down, and ripped that sign off his neck. I crumpled it in my fist.

“I am calling security!” Halloway shrieked. “And the school board! We will have you removed.”

I finally turned to look at her. I just smiled. It wasn’t a nice smile. “Go ahead,” I said. I pointed a greasy thumb at the patch stitched in white thread on my leather vest, right over my heart. “You tell ’em who I am. Tell them you just did this to the son of the School Board’s new President.”

Her mouth opened and closed like a fish. The name on the patch wasn’t flashy. It just said “Mark Rivington.” But underneath it, smaller, were the words “Hawthorne District School Board.”

The fury in her eyes flickered, replaced by a cold, dawning panic. The other kids in the room were dead silent. You could have heard a pin drop on the worn linoleum.

I scooped Toby up in my arms. He buried his face in my neck, his small body still trembling. I could feel his tears soaking into the collar of my shirt.

“Let’s go, buddy,” I whispered, my voice soft now, only for him. “We’re done here for today.”

I turned and walked towards the door, not giving Halloway another glance. As I passed her desk, I dropped the crumpled cardboard sign onto her perfectly organized planner. It landed with a soft, pathetic thud.

The principal, Mrs. Davison, met me in the hallway. Her face was pale. The receptionist must have called her after all.

“Mark,” she started, her voice strained. “What on earth is going on?”

I just held my son tighter. “You tell me, Sarah. You tell me why one of your teachers thinks this is an acceptable way to treat a child.”

I didn’t wait for an answer. I carried Toby right out the front doors, past the startled receptionist, and into the sunlight. The roar of my motorcycle starting up was the only answer I gave them.

Back at home, I sat Toby on the kitchen counter and got him a glass of juice. He was quiet, just staring at his worn sneakers.

“It was an accident,” he mumbled. “The blue paint.”

“I know it was, kiddo,” I said, wiping a smudge of dirt from his cheek. “You don’t ever have to worry about her again. I promise.”

He looked up at me, his blue eyes wide and serious. “Are you really the president?”

I let out a small laugh. “Yeah. I guess I am.”

It wasn’t something I advertised. Most people in town knew me as the guy who ran Rivington’s Garage. They saw the tattoos snaking up my arms and the leather vest I wore for my motorcycle club, the Iron Heralds. They didn’t see the man who spent his nights reading books on education policy.

It all started a year ago. Toby was struggling to read. His first-grade teacher said he was lazy, that he wasn’t trying. My wife, Laura, passed away a few years back, so it was just me and him against the world. I knew my son wasn’t lazy.

I took him to a specialist. They diagnosed him with severe dyslexia. It wasn’t a lack of effort; his brain was just wired differently.

I went to the school with the report. I tried to explain. They nodded and smiled and filed it away. Nothing changed. The resources were non-existent. The teachers weren’t trained.

So I started going to school board meetings. At first, I just sat in the back, listening. I was the only parent there who wasn’t wearing a suit. They looked at me like I was a bug.

But I kept showing up. I started speaking. I didn’t use fancy words. I just told them about Toby. I told them about the other kids I knew whose parents were too busy working two jobs to come and fight.

Turns out, a lot of people were listening. The other parents. The mechanics at my shop. The guys in my club. The quiet ones who felt like the system had forgotten them.

When a board seat opened up, they encouraged me to run. I laughed at first. Me? A grease monkey on the school board? But they were serious. They printed flyers. They knocked on doors. The Iron Heralds, my “scary” biker club, held a bake sale to raise funds.

I won. By a landslide. Two weeks ago, the other board members, impressed by my passion or maybe just tired of arguing with me, voted me in as the new president. I hadn’t even had my official photo taken yet.

My phone buzzed. It was Sarah Davison. I let it go to voicemail. I needed to focus on my son.

Later that evening, after Toby was asleep, I listened to the message. Sarah was apologetic, flustered. She’d called an emergency meeting for the next morning. Mrs. Halloway was on administrative leave pending a full investigation.

The next day, I didn’t wear my vest. I wore a clean collared shirt and my work jeans. I still felt out of place walking into the district office, but my steps were steady.

Sarah and Halloway were already in the conference room. Halloway looked like she hadn’t slept. Her usual severe bun was messy, and her eyes were red-rimmed.

I sat down and got straight to the point. “I don’t want your apologies,” I said, my voice level. “I want to understand why. Why you would do that to any child, let alone one you know has a learning disability.”

Halloway flinched. She looked at Sarah, then at the table. For a long time, she said nothing.

“It’s not an excuse,” she finally whispered, her voice cracking. “But my own son… he was like Toby. Always struggling, always a step behind. I didn’t understand it back then. His father and I… we thought he was being difficult. We pushed him. We disciplined him.”

She took a shaky breath. “He dropped out of school when he was sixteen. We haven’t spoken in ten years. Every time I see a child struggling, a part of me… a broken, angry part of me… sees him. I see my own failure as a mother.”

The room was silent. I looked at this woman, who had humiliated my son, and I didn’t feel the rage I expected. I just felt a deep, profound sadness. Her cruelty wasn’t born from malice. It was born from a pain she’d never dealt with.

This was the twist I never saw coming. It wasn’t a monster in that classroom. It was a heartbroken mother who had turned her own regret into a weapon against children.

It didn’t excuse what she did. Not for a second. But it changed things.

“You need help, Mrs. Halloway,” I said quietly. “What you did was wrong, and there have to be consequences. But you’re right. That’s not a teacher in that classroom. It’s a grieving parent who needs to heal.”

The investigation went forward. Halloway resigned before they could fire her. The board, with my lead, didn’t just stop there.

We used the incident as a catalyst for real change. We pushed through a massive new budget initiative. We hired two full-time dyslexia specialists for the district. We mandated comprehensive training for every single teacher on how to identify and support students with learning differences.

I didn’t do it with anger or threats. I did it by telling stories. I told them Halloway’s story, without using her name. I told them Toby’s story. I told them the stories of a dozen other kids.

A few months passed. Toby was in a new classroom with a new teacher, a young man named Mr. Avery who was brilliant. He used colored overlays to help Toby read. He let him use a computer to type his assignments. He praised his creativity and his unique way of seeing the world.

My boy was transforming. The nervous tremor in his hands was gone. He started raising his hand in class. He came home with a smile on his face, excited to tell me about the book they were reading.

One afternoon, I was at the shop when Frank, the school janitor who had texted me, stopped by. He wasn’t in his usual work uniform.

“Just wanted to say thank you, Mark,” he said, twisting a ball cap in his hands.

“For what, Frank?” I asked, wiping grease from my hands. “You’re the one I should be thanking. If you hadn’t texted me…”

He shook his head. “It’s more than that. My granddaughter, Sophie. She’s in the third grade. She has the same thing as Toby. Dyslexia. All those new programs you pushed for? The new specialist? It’s changing her life.”

He looked me right in the eye. “I saw what was happening to your boy and I saw what was happening to mine. I knew you were the only one who would actually do something about it. Not just yell, but fix it.”

That was the second twist. The text wasn’t just a friend helping a friend. It was a grandfather’s desperate plea, put in the hands of the one man he believed could make a difference. His faith in me was humbling.

The following spring, the Iron Heralds hosted our annual “Ride for Reading” charity event. We always raised a bit of money for the local library. This year, I directed all the funds to the school district’s special education department.

The whole town showed up. Parents, teachers, even Mayor Thompson. They saw a hundred bikers in leather and denim, but they weren’t scared. They were cheering. They were donating. Mrs. Davison, the principal, was sitting at the front table, selling raffle tickets.

I stood on a small stage, a microphone in my hand. I looked out at the crowd, at the families, at my biker brothers. I saw Toby in the front row, sitting next to Sophie, Frank’s granddaughter. They were sharing a book. Toby was pointing at the words, sounding them out, and Sophie was listening, smiling.

My voice was a little thick when I started to speak. I told them that a community isn’t measured by its fancy buildings or its tidy lawns. It’s measured by how it treats its most vulnerable. It’s measured by how it lifts up its children.

I realized then that true strength wasn’t in the roar of an engine or the leather on my back. It was in the quiet resolve to fix what’s broken. It’s in the courage to turn pain, whether it’s your own or someone else’s, into a purpose.

That sign of shame was meant to break my son. Instead, it built a bridge. It connected a biker dad, a regretful teacher, a hopeful grandfather, and an entire town that just needed a reason to come together.

The real reward wasn’t just seeing my son heal; it was seeing him help someone else do the same. The cycle of hurt had been broken, replaced by a cycle of compassion. And that was a legacy worth fighting for.