Food prices have been on the rise across the country due to inflation. As observed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the cost of foods such as bread, eggs, and meat surged over 10 percent from June 2021 to June 2022. As a result, many of us are looking for smart ways to make the most out of our grocery budget.

A great approach to help your hard-earned money go further is to get a grip on those sometimes puzzling food labels.

By doing so, you can stop yourself from throwing away food that’s still perfectly good. A study from the Food Marketers Institute in 2011 revealed that many people choose to dispose of food that is past its expiration date, erring on the side of caution. About 91 percent of participants said they sometimes discarded food after its “sell by” date out of safety concerns, and 25 percent reported doing so consistently.

This cautious attitude likely contributes to the staggering 30–40 percent of our nation’s food supply going to waste each year, as pointed out by a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) study in 2014.

To make that clearer: According to the 2014 USDA study, around 133 billion pounds and $161 billion worth of food went to waste in 2010 alone.

Understanding food labels doesn’t just help your pocketbook; it also benefits the environment. Inger Andersen from the United Nations Environment Programme points out that food waste significantly contributes to the major issues of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution, as explained in the 2021 UNEP Food Waste Index Report.

Navigating the Confusion Around Food Expiration Dates

You’re definitely not the only one who finds the various food labels bewildering. A 2007 survey featured in the Journal of Food Protection highlighted this widespread misunderstanding among consumers.

For example, less than half of the survey’s participants correctly defined what a “sell by” date meant, with about a quarter wrongly believing it was the last day the product was considered safe to eat.

A significant reason behind this confusion is the lack of a federal regulation or standard definition for food labels, says Dana Gunders from ReFED, an organization devoted to eliminating food loss and waste.

Gunders is among those advocating for a unified policy on product dates because the current laws vary by state, adding to the puzzle.

Decoding the Different Food Expiration Dates

It’s important to know that common labels such as “best by,” “use by,” and “sell by” are not indicators of safety, explains Amy Shapiro, RD from Real Nutrition in New York City.

These dates are mainly manufacturers’ suggestions for when the product will be at its best quality. “Best-by and use-by dates are really designed for the look of the product and the palatability of the product,” says Bill Marler, a Seattle-based food safety attorney.

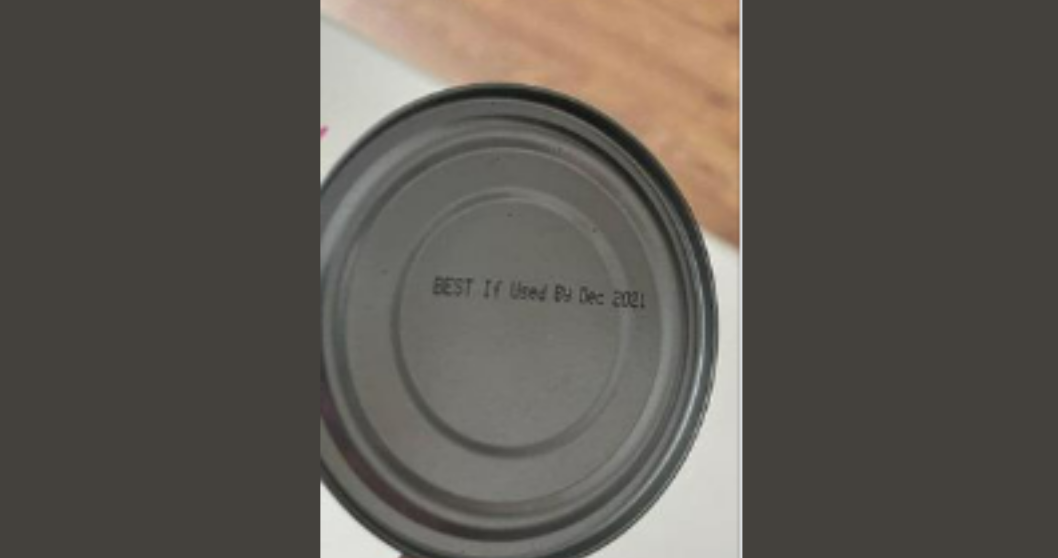

Best if Used By/Before

A label that reads “best if used by/before” indicates when the food will taste and look its best. It doesn’t mean that the food is unsafe to eat after that date—it just might not taste as great. This label can be found on various types of food, including those that are frozen, refrigerated, canned, and boxed.

Use By

“Use by” represents the last date for the product to be at its peak quality, according to the FSIS. It’s important to note that, except for baby formula, these items are still safe beyond this date. Foods that spoil quickly such as meats, dairy, and ready-to-eat items typically carry this label.

Sell By

The “sell by” label is meant for retailers, indicating the last day the item should be displayed for sale. You can still consume products past this date.

When to Say Goodbye to Food

Do you need to toss food once these dates have passed? The answer is no—unless the food shows obvious signs of spoilage. Look out for off smells or changes in color, consistency, or texture, advises the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

However, when it comes to baby formula, it should not be used past its “use-by” date. This is the only food category that carries this requirement, enforced by the FDA.

“Until that declared date, the infant formula will contain no less than the amount of each nutrient declared on the product label and will otherwise be of acceptable quality,” states the federal agency.

In terms of canned goods and pantry staples, here’s some reassurance. The date on the can simply marks its peak quality, but these items can last far longer. The USDA mentions that low-acid foods like canned tuna or vegetables hold their best quality for two to five years. High-acid foods like pickles and fruit, on the other hand, stay good for 12 to 18 months.

In fact, canned foods can last even longer under the right conditions. “If cans are in good condition (no dents, swelling, or rust) and have been stored in a cool, clean, dry place, they are safe indefinitely,” the agency notes.

Lastly, freezing is an excellent option. If you freeze food while it’s still fresh, it can be safe to eat indefinitely, according to the FSIS. This includes meats, casseroles, soups, and frozen dinners, because low temperatures prevent bacterial growth.

Concerns About Foodborne Illness

While being overly cautious about food labels may help prevent bacterial infections, it’s essential to stay informed about certain bacteria. “The longer something’s around—if it has bacteria on it—the more likely it is that the bacterial growth will reach a level that will make you sick,” says Marler.

“There’s a certain infectious dose that will do that and it varies from bacteria to bacteria,” he explains further.

One of the more worrying bacteria is listeria, which grows well even at refrigerator temperatures. This means “the longer you keep it in your refrigerator, the more likely it is that it’ll reach an infectious dose high enough to make you sick,” Marler points out.

Even though food labels aren’t intended as indicators of food safety, it’s wise to take note of them in cases of potential listeria contamination.

If contamination is already present, further refrigeration won’t mitigate the risk.