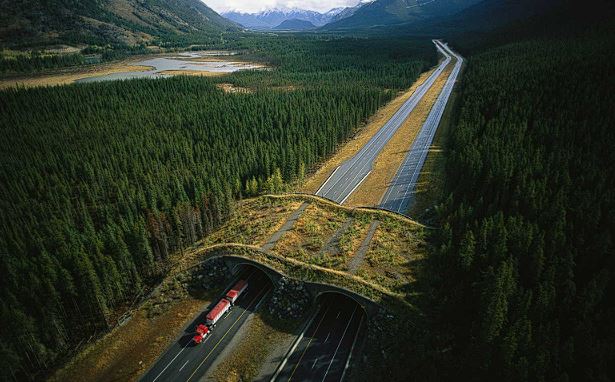

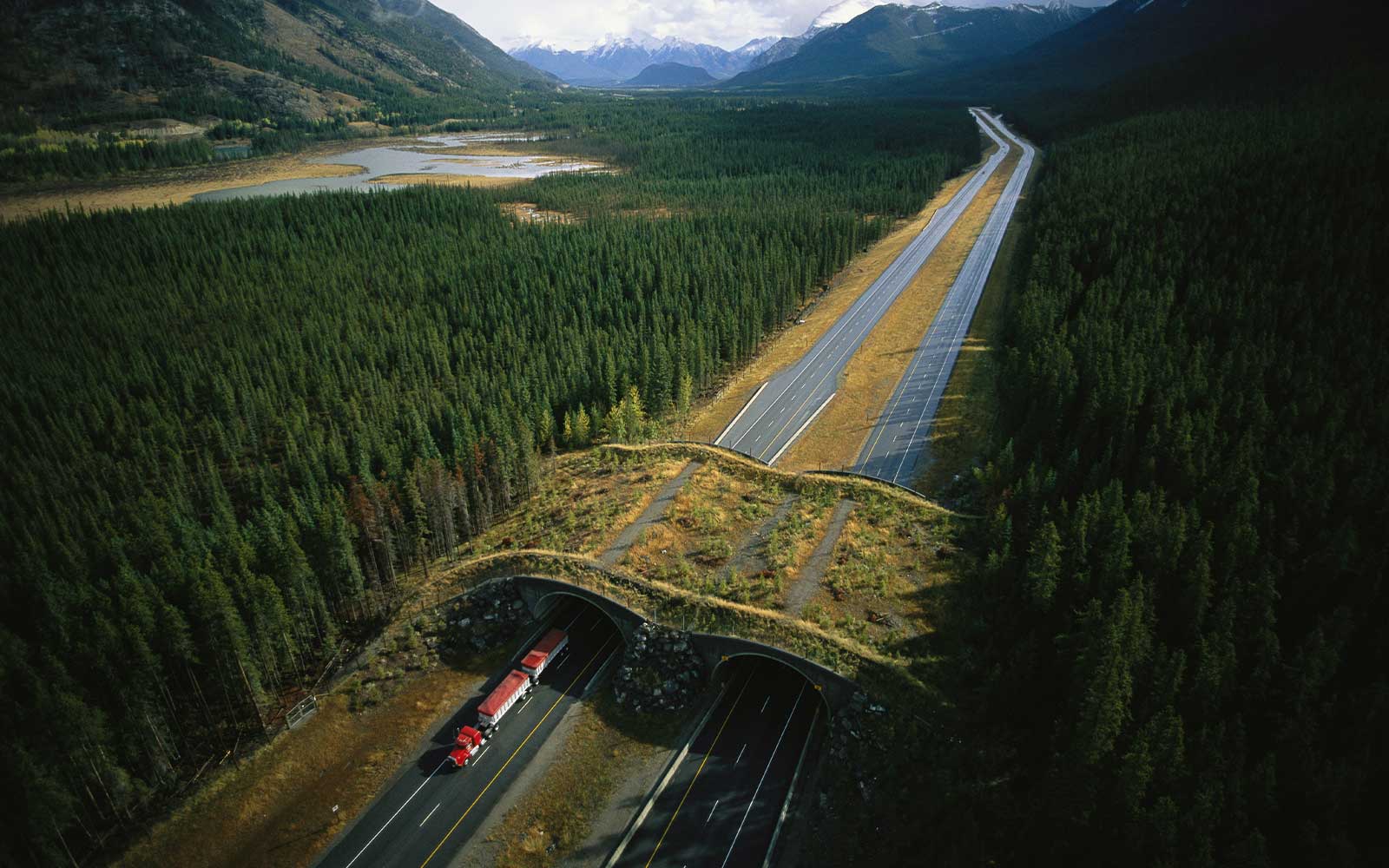

Why did the bear cross the Trans-Canada Highway? We may never know, but thanks to the Banff Wildlife Crossings Project, there’s a good chance it made it to the other side.

When the 82-kilometre section of the Trans-Canada Highway that runs through the Rocky Mountains in Banff National Park was built in the early 1950s, it wasn’t expected to be the major artery it is today. But as park visitation increased, traffic volume surged—and so did highway-related wildlife mortality.

Engineering a solution

In 1978, Public Works Canada proposed twinning the section of the highway that runs from the east gate of the park to the Banff townsite to improve the safety of motorists and animals. The twinning ultimately extended to Castle Junction by 1997 and the British Columbia border by 2014.

Along with the twinning came an interesting engineering opportunity through Parks Canada—the construction of wildlife crossings to decrease vehicle collisions and restore critical migration routes that had been blocked by the highway.

Banff’s first two wildlife overpasses were built in 1996 at a cost of $1.5 million each. A series of underpasses followed, tunnelling beneath the highway to provide a safe alternative.

Combined with fencing to keep the animals off the road, the structures have reduced animal-vehicle collisions in the area by more than 80%—and by more than 96% for elk and deer alone.

A perfect fit

To passing motorists, the overpasses look like any other highway bridge: solid concrete arching over the highway. But catch a glimpse of the top, and it’s clear they cater to a different crowd—the forest stretches from one side to the other, uninterrupted by the highway below.

Fencing along the sides ensures the fauna stay out of harm’s way.

Long-term research and monitoring of the structures—which started in 1996 and is ongoing—shows that more than 12 species—including deer, lynx, coyotes, wolves, wolverines, and bears—use the crossings, even changing their behaviour to do so.

Elk were the first large species to use the crossings, testing them out while they were still under construction.

Monitoring also shows that different species have different preferences: grizzly bears, deer, moose, and elk favour the open air of the overpasses, while cougars and black bears prefer the cozy coverage the tunnels provide.

The crossings also help maintain genetic diversity in wildlife populations, reconnecting the habitat on either side of the highway and allowing different groups of the same species to interact.

Branching out

From its humble beginnings, the Banff Wildlife Crossings Project has grown to include 38 underpasses and six overpasses, spanning from Banff National Park to the British Columbia border.

The resounding success of the first large-scale highway mitigation project for wildlife in the world has positioned Banff National Park as an international leader in road ecology.

Scientists from around the world have visited the park to gain inspiration and education, returning home to develop crossings for their own wildlife populations, such as tigers in Asia, howler monkeys in Costa Rica, and jaguars in Argentina.

As you travel through Banff National Park, the animals are travelling too—over your roof and under your wheels. Wildlife crossing structures and highway fencing in the park have reduced wildlife deaths by more than 80%.

This is a tiny fraction of the amazing photos of wildlife that have been captured on wildlife crossing structures that span the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park.